In January of 2021, Alacrity Canada’s first Cleantech market research intern, Mary Elebijo, put together a report titled “Carbon Market, Carbon Market Jurisdictions, and Carbon Credits Trading.” In this research report, she examined the global state of carbon management and the interplay of carbon market jurisdictions in Canada and around the world. Find a summary of the most exciting snippets from her report compiled below, but first, a couple of important definitions to help explain the difference between carbon credits, and trading and offsetting.

Carbon market definitions

Carbon credits: A carbon credit is a certificate that represents one ton of carbon dioxide. It is a credit because it permits the person in possession of the credit to emit one ton of carbon dioxide or an equivalent measurement of another GHG in a cap-and-trade system. Carbon credits provide a means by which to reward companies who reduce their carbon emissions and incentivize heavy carbon or GHG emitters to re-work their processes to reduce their carbon emissions. Carbon credits are considered by many to be an essential mechanism in the fight against climate change globally because they also provide an avenue for inherently carbon-heavy industries to still function in the short-term, just at an increased cost, also meaning that over time investors and industry gravitate towards more sustainable and less carbon heavy activities.

Carbon credit trading: Carbon credits are tradeable in both private and public markets. The price of carbon credits fluctuates in the same way that the price of any commodity does.

Carbon offsetting: Another form of carbon trading is the practice of carbon offsetting, which is a very useful carbon management mechanism, but also one which requires intense oversight and regulation to ensure that carbon offsets are accurately calculated and guaranteed indefinitely.

Generally accepted criteria for a carbon offset to qualify as tradable on the carbon market:

- must be real and present an actual and accurate reduction in emissions

- must be executed in addition to, not instead of, emissions reductions

- must be permanent, meaning that the emissions reductions are non-reversible (at least for a certain number of years)

- must be verifiable within established auditing and vetting processes

- must be quantifiable

- must be enforceable, meaning that the ownership of the offset it only claimed by one actor and that the owner of the offset is solely responsible for the validity of the offset

The State of the Global Carbon Market

The emission of greenhouse gases (GHG) caused largely by human activity has been established as having a warming effect on Earth’s climate. The four gases which cause the greatest greenhouse effect, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency, are nitrous oxide (NOx), methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), and fluorinated gases. Together, they fall under the scope of a carbon tax.

CO2 emissions make up a large part of the global greenhouses gases that accelerate climate change.

Global Factors

The Kyoto Protocol, created by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), came into effect in 1997 and introduced a variety of measures aimed at reducing GHG emissions. One of those measures was an international call to action regarding carbon pricing. Carbon pricing provides a financial disincentive for actors to emit large amounts of carbon and a financial incentive for actors to cut their emissions.

One of the core issues with carbon pricing is that governments around the world have, to date, largely failed at collective action on climate change. Due to this, a substantial and unavoidable disincentive exists for any one government to price carbon sufficiently high to curb greenhouse gas emissions because doing so would dash their economic competitiveness globally. Another issue is that, practically speaking, implementing and enforcing a carbon price is more complex than it might initially sound.

Another socio-economic issue relating to the global carbon economy is that of developing economies which, as demonstrated in climate change research, already bear the burden of the effects of climate change. These developing economies are unfairly positioned to compete in a global economy that functions with a price on carbon and a cap-and-trade system. This is because industrial infrastructure in developing economies is less developed and the capacity for their governments to provide seed funding for innovation and crucial funding support for early adapters is limited. The low adaptation capabilities of developing economies will result in climate policies imposing a disproportionately high burden on low-income nations if not properly counter-balanced by appropriate compensation or support measures. For this reason, the establishment of a market for carbon is not an easily transferable policy mechanism globally. One solution to this inequity issue is to tax emissions generated by developing economies at a lower rate than developed economies.

The economic disadvantage of carbon taxation for developing economies is rendered only more problematic by the reality that the vast majority of global GHG emissions have been produced by developed economies over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries. Constructing a global carbon management system that ensures that all emissions-reducing nations gain financially is absolutely essential. Without a clear economic case for the eventual benefits of the investments of time and money into re-making entire economies, securing the support of both developed and developing economies will not be possible.

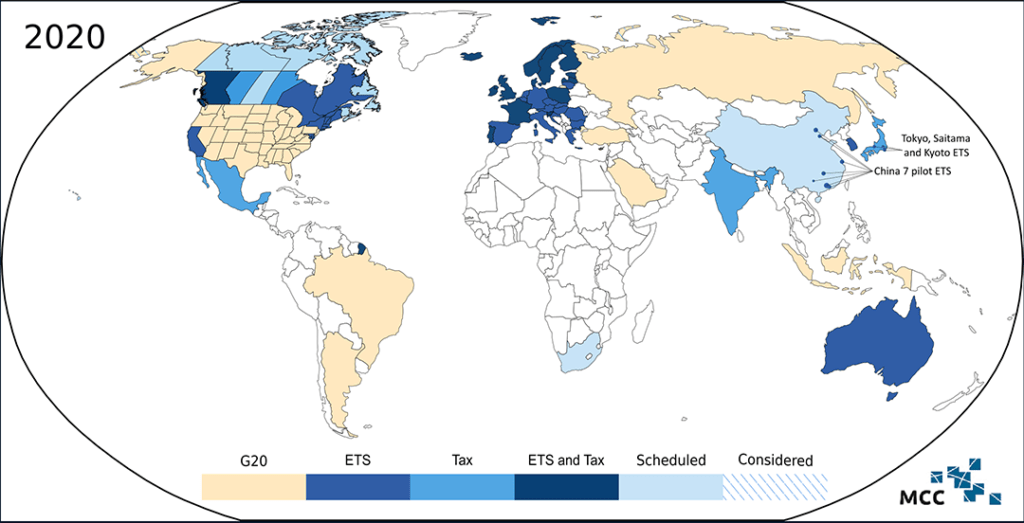

The state of the global carbon market in 2020, according to Our World in Data.

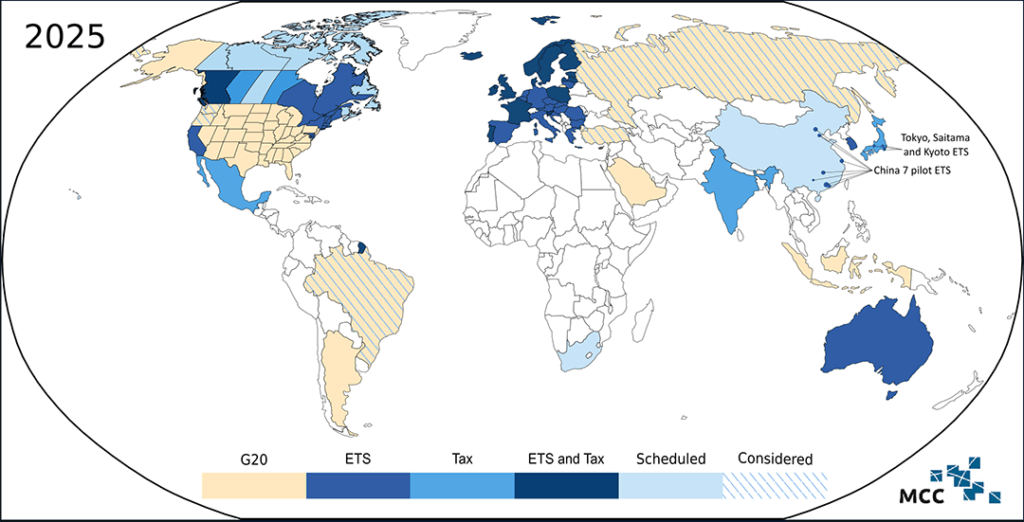

The projected state of the global carbon market by 2025, according to Our World in Data.

The European Union: The World’s First Major Carbon Market

The European Union’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is the world’s first major carbon market and remains the biggest one to date. It has become an example of how emissions trading globally could be structured and is the cornerstone of the EU’s strategy to tackle climate change by providing a financial incentive for the biggest emitters to cut back their emissions. The EU’s ETS “proves that putting a price on carbon is possible and makes economic sense,” according to this video produced by the EU ETS.

According to a report published by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), analysts have found that the EU’s ETS can be credited with reducing GHG emissions within the EU by -10% from 2005-2012, and that the ETS has had “no negative impact on the economic performance of regulated firms.” This demonstrates that concerns about the EU ETS hindering the competitiveness of firms under its jurisdiction have been “vastly overplayed.” In fact, the study finds that firms operating within the framework of the ETS have experienced increases in revenue and the value of fixed assets during the period of observation.

The Problem of Global Coordination

Despite the EU’s efforts to implement the Emissions Trading System, the global market for carbon emissions trading remains largely disorderly and uncoordinated. There is no standard system for pricing or managing an inventory of carbon emissions and the variety of interests and needs among economies makes establishing any sort of equitable solution highly complex. Additionally, a key mechanism in carbon emissions management is carbon offsets, which can be extremely challenging to verify and guarantee and which are mostly unregulated at present. This episode of Bloomberg’s Quicktake provides a quick glimpse into the murkiness of carbon offsets globally.

The lack of coordination in the carbon emissions market is contrasted by the systematized global financial sector. In order for humans to make real strides towards sufficiently large emissions reductions, we need a global system and standard market where carbon can be traded – just as currencies, bonds and equities currently are – in a regulated and transparent way. The issue of equity in this scenario would still exist and thus a system for developing financial incentives and compensations would need to be established to ensure that developing economies are not disadvantaged on yet one more economic plane.

This article in The Narwhal highlights how the rules for the international trade of emissions reductions credits named under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement still need to be established, especially given that the implications for jurisdictions trying to reach their emissions targets are so great.

Current carbon emissions mitigation schemes

There are a wide variety of carbon emissions mitigation schemes that can be used to help generate carbon credits. These include:

- Renewable energy sources

- Agricultural innovations and improvements

- Afforestation and reforestation

- The capture of transient emissions

- Waste disposal and handling

- Mining and metal production innovations and improvements

- Wastewater treatment

- Manufacturing and chemical industries innovations and improvements

- Transport innovations and improvements

- Methane capture

The State of the Canadian Carbon Market

On March 25th, 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada voted 6-3 in favour of the federal government’s right to impose nationwide carbon pricing standards on the Canadian carbon market. The decision “allows Ottawa to push ahead with its ambitious plan to ensure every province and territory has a price on carbon,” according to the CBC. The ruling will be most consequential for the state of carbon taxing in Alberta, Ontario, and Saskatchewan, the provinces most opposed to a provincial carbon tax scheme. The ruling also means that the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act carbon pricing law, which came into force in 2018, will stand.

According to global financial services provider, Northern Trust, Canada currently has one of the more ambitious carbon pricing programs in the world. Though this may be true, Canada has a mixed history on climate action, exemplified by Canada’s departure from the Kyoto Protocol in 2011 due to its failure to achieve any of the targets set out when it joined in 2002. Despite joining the protocol in the early 2000s, the Canadian government never actually passed comprehensive legislation to regulate emissions, meaning that there were no policy mechanisms in place to encourage any changes in behaviour. Two more key factors that have delayed action include:

- Canadian governments have historically hesitated to take serious steps in reducing GHG emissions without similar actions also being taken by the United States because of the anticipated short-term negative impact that these emissions reducing actions would have on the Canadian economy.

- The Canadian economy is heavily resource extraction-based and, as a result, the reduction of GHG emissions will require a massive redistribution of jobs from the fossil fuel industry (and other resource extraction industries).

Nevertheless, the federal government recently announced more aggressive targets, declaring that it would slash GHG emissions by at least 40% from 2005 levels by the year 2030. Detailed plans about how this reduction will be achieved are currently in the works.

Closer to Home: The BC Carbon Tax

The BC Carbon Tax works to incentivize companies and businesses to reduce their GHG emissions. A recently created initiative to further encourage emissions reductions is the CleanBC Industrial Incentive Program (CIIP). Established in 2019, the program requires large industrial facilities to report their GHG emissions in accordance with the Greenhouse Gas Industrial Reporting and Control Act (GGIRCA). This program rewards industrial facilities that reduce their emissions by providing them with payments to offset some of the tax they pay for their still existing carbon emissions.

Carbon Reporting in the Private Sector

Carbon emissions reporting and disclosure in the private sector occurs at present on a voluntary basis. In order for voluntary reporting to work, there needs to be a substantial financial reward for companies who choose to publish this data and who make concerted efforts to reduce their carbon footprint.

Energy production, heavy industry, and transport are leading sources of greenhouse gas emissions. The carbon market can be used to encourage faster transition of economies to low or no emissions as an important step in mitigating the global impact of climate change.

While emissions management policy at the global level is still in its nascence, there is increasing awareness among communities worldwide that climate change (among other environmental issues) is one of the greatest threats to life on Earth today and in the future. As governments begin or continue to create policy that rewards low-emitters and disadvantages high-emitters, and as more individuals and investors in the private sector increasingly look to hold industry to account for their emissions, private and public actors around the world are taking greater action to reduce the carbon footprint of their operations. An emerging sector contributing to the low-carbon economy is that of alternative fuel sources such as hydrogen.

Where Is the Carbon Market Going next?

A challenge that we will continue to face when it comes to a coordinated global carbon market is that nations around the world will continue to resist seriously regulating or closing down carbon-heavy industries because of the short-term economic impacts of doing so. As long as high GHG emissions are seen as non-threatening to the future success and existence of businesses, companies globally will not do enough to help reach the global emissions reductions that are required to limit global warming by the two degrees Celsius set out in The Paris Agreement of 2016.

In order for the carbon market to really become a vehicle for change at a global level, a concerted effort must be made by more companies, investors, and governments to act on GHG emissions reduction targets sooner rather than later. The need for a worldwide framework and regulatory body is evident in the current state of the global carbon market.